Motivation for Modern Probability using Axiomatic Approach

Classical probability theory defines probability using equally likely outcomes, making it suitable for finite cases like dice rolls and coin flips. However, it struggles with infinite sample spaces and complex probability distributions. In contrast, modern axiomatic probability theory, formalized by Kolmogorov in 1933, uses measure theory and sigma-algebras to define probability more rigorously. It is based on three axioms: non-negativity, total probability equaling one, and countable additivity for disjoint events. This approach allows for handling infinite and continuous probability distributions, making it essential in advanced fields like stochastic processes, statistical mechanics, and finance. While classical probability is intuitive and combinatorial, modern probability provides a more general and rigorous foundation applicable to both discrete and continuous cases.

In this article, we will study a problem with infinite sample space. The idea is to motivate the need for an axiomatic approach to probability theory.

Bertrand paradox: Random Chord on a unit circle

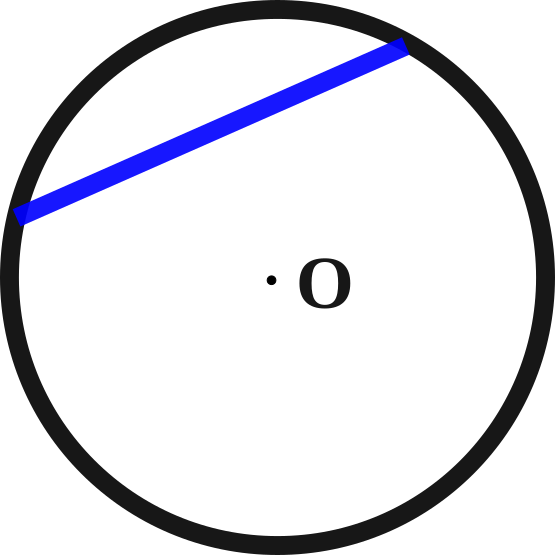

Consider a unit circle. Suppose we draw a chord randomly and uniformly on this circle. Find the probability that the length of the chord is greater than \(\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\).

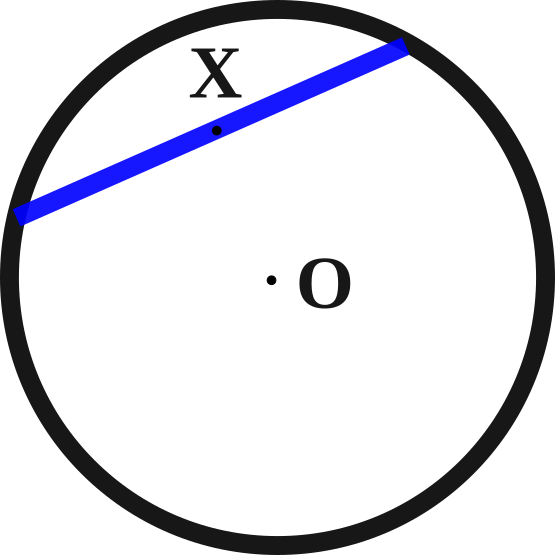

Solution 1

Draw an arbitrary line \(L\) connecting the center of the circle, say \(O\) to its circumfrence. Pick a point \(X\) on line \(L\) randomly and uniformly. Draw a chord on the unit circle with point \(X\) as the middle point. This is the first approach to choosing a random chord. Observe that \(d(X,O)\geq \frac{1}{2} \Rightarrow\) Length of the chord is greater than \(\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\). Therefore, the probability of drawing a chord of length greater than \(\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\) is equal to the probability that \(d(X,O)\geq \frac{1}{2}\) which is equal to \(\frac{1}{2}\).

Solution 2

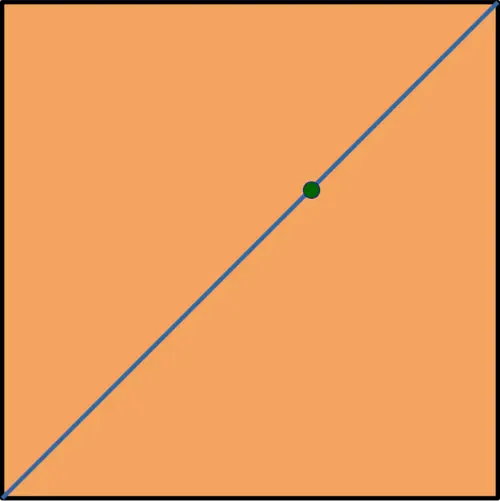

Pick a point \(X\) inside the circle randomly and uniformly. Draw a chord on the unit circle with point \(X\) as the middle point. This is the second approach to choosing a random chord. Observe that \(d(X,O)\leq \frac{1}{2} \Rightarrow\) Length of the chord is greater than \(\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\). Therefore, the probability of drawing a chord of length greater than \(\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\) is equal to the probability that \(d(X,O)\leq \frac{1}{2}\) which is equal to \(\frac{1}{4}\).

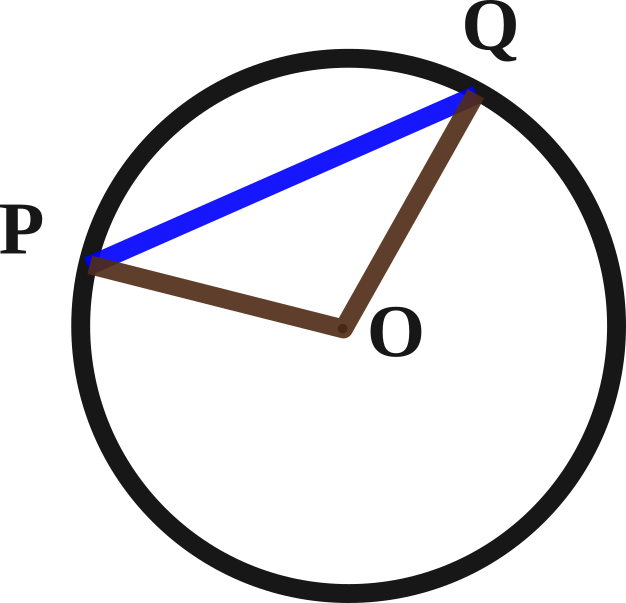

Solution 3

Pick two points \(P,Q\) on the circumfrence of the unit circle randomly and uniformly. Draw a chord on the unit circle with points \(P,Q\) as its end points. This is the third approach to choosing a random chord. Let \(O\) denote the center of the circle. Observe that \(180^{\circ}\geq\angle{POQ}\geq 120^{\circ} \Rightarrow\) Length of the chord is greater than \(\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\). Therefore, the probability of drawing a chord of length greater than \(\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\) is equal to the probability that \(180^{\circ}\geq\angle{POQ}\geq 120^{\circ}\) which is equal to \(\frac{1}{3}\).

Conclusion

The three approaches above yield three different answers. This may sound like a paradox but three different answers has do with how we measure space. Therefore, in the modern probability, we employ an axiomatic approach. In axiomatic approach, one avoids counting or measuring. It is assumed that someone has already defined the probability space satisfying certain axioms.Author

Anurag Gupta is an M.S. graduate in Electrical and Computer Engineering from Cornell University. He also holds an M.Tech degree in Systems and Control Engineering and a B.Tech degree in Electrical Engineering from the Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay.

Comment

This policy contains information about your privacy. By posting, you are declaring that you understand this policy:

- Your name, rating, website address, town, country, state and comment will be publicly displayed if entered.

- Aside from the data entered into these form fields, other stored data about your comment will include:

- Your IP address (not displayed)

- The time/date of your submission (displayed)

- Your email address will not be shared. It is collected for only two reasons:

- Administrative purposes, should a need to contact you arise.

- To inform you of new comments, should you subscribe to receive notifications.

- A cookie may be set on your computer. This is used to remember your inputs. It will expire by itself.

This policy is subject to change at any time and without notice.

These terms and conditions contain rules about posting comments. By submitting a comment, you are declaring that you agree with these rules:

- Although the administrator will attempt to moderate comments, it is impossible for every comment to have been moderated at any given time.

- You acknowledge that all comments express the views and opinions of the original author and not those of the administrator.

- You agree not to post any material which is knowingly false, obscene, hateful, threatening, harassing or invasive of a person's privacy.

- The administrator has the right to edit, move or remove any comment for any reason and without notice.

Failure to comply with these rules may result in being banned from submitting further comments.

These terms and conditions are subject to change at any time and without notice.

Similar content

Past Comments